“Those who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it.”

– George Santayana

Before the long queues to buy a litre of fuel for the sum of a thousand Naira and sometimes even higher became the sad norm, there was the oil boom — a time in Nigeria’s history steeped with hope, wealth, and the promise of prosperity. The streets were lined with the bright lights of new developments, and the air was thick with the optimism of a nation on the brink of greatness.

It was an era when the nation’s fortunes seemed to be irrevocably tied to a black, viscous liquid that flowed beneath its soil. But as the decades rolled on, that optimism gave way to a harsh reality. So, what changed?

Crude Oil: Understanding How it’s Formed and Works

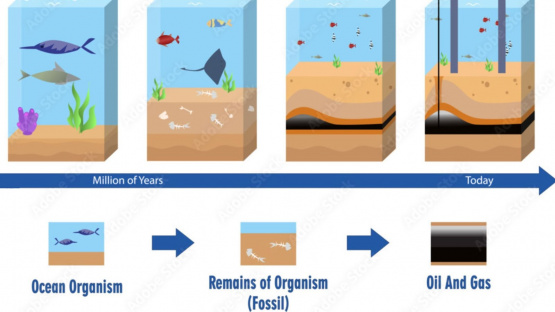

Before we delve into the story being discussed today, it’s important to understand the science behind crude oil formation and how the derivatives from it work, as well as their benefits and why they’re so sought after.

Crude oil is a fossil fuel formed from ancient plants and animals buried deep within the Earth’s crust. Over millions of years, heat and pressure transform these organic materials into a complex mixture of hydrocarbons. This mineral resource is then refined into various products, including petrol, diesel, kerosene, and aviation fuel, which power our vehicles, industries, and homes.

Its unique combination of high energy density, versatility, and relatively low cost drives global demand. However, this demand also creates an environment vulnerable to corruption, mismanagement, and environmental degradation.

The Discovery of Crude Oil and The Boom Years

“Nigeria’s problem is not money, but how to spend it.”

– Yakubu Gowon

The story of Nigeria’s oil boom begins in the quiet creeks of the Niger Delta, where in 1956, Shell-BP struck oil in commercial quantities at Oloibiri, a small community in what is now Bayelsa State. For a country that had been largely agrarian, relying on cocoa, groundnuts, and palm oil as its primary exports, the discovery of oil seemed like a miracle. Black gold, they called it — and with good reason. By 1958, Nigeria was exporting crude oil, and by the late 1960s, production had ramped up significantly.

The 1970s ushered in a new era for the country. Nigeria had struck gold – or more accurately, black gold. The global demand for oil was rising, and Nigeria was poised to ride the wave. And ride it did, as the country’s entry into OPEC in 1971 marked the beginning of an extraordinary transformation.

But it was the geopolitical shifts of the decade, particularly the 1973 Arab-Israeli War and the resulting oil embargo, that truly set the stage for Nigeria’s oil boom.

Oil prices soared, and so did Nigeria’s fortunes. The government, flush with petrodollars, embarked on ambitious and somewhat grandiose projects — highways were constructed, skyscrapers pierced the Lagos skyline, bridges spanned rivers that had long been barriers to trade, and the promise of a new Nigeria seemed within reach. In 1977, the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) was established to manage the nation’s burgeoning oil wealth.

However, beneath the surface of this newfound prosperity, there were cracks.

The Seeds of Decline: Corruption and Mismanagement Begins to Take Root

With great wealth came great temptation.

As oil revenues flowed into government coffers, so too did the temptations that come with sudden wealth. Corruption began to take root, fueled by the easy money that oil provided. Public officials, entrusted with the nation’s wealth, diverted funds meant for development into their personal accounts. The grand infrastructure projects, once symbols of progress, became monuments to mismanagement and waste.

The military governments of the time, having come to power through coups, were particularly susceptible to this corruption. Without the checks and balances of democratic institutions, accountability became a scarce commodity – perhaps even scarcer than the oil itself.

The story of Ajaokuta Steel, a massive industrial project meant to diversify Nigeria’s economy, is one of many that exemplifies this era. Billions of dollars were poured into the project, but it never materialized into the industrial powerhouse it was meant to be. Instead, it became a symbol of the inefficiency and corruption that plagued the nation.

As succeeding governments became increasingly dependent on oil, other sectors of the economy, particularly agriculture, were neglected. The once-thriving groundnut pyramids of Kano and the cocoa farms of the southwest were abandoned as everyone rushed to share in the oil wealth. Why toil in the fields when black gold flowed so freely? This shift marked the beginning of what economists call the “Dutch Disease” – a paradoxical situation where a boom in one sector leads to the decline of others. As oil dominated, agriculture withered, and with it, the diversified economic base that had sustained the nation. This reliance on a single resource set the stage for economic instability, as the nation’s fortunes became tied to the volatile swings of global oil prices.

The Aftermath: A Legacy of Dependency and Instability

By the 1980s, the dream of the oil boom had soured. Global oil prices plummeted, and Nigeria, with its economy now heavily dependent on oil, was plunged into crisis. The wealth that had once seemed limitless evaporated, leaving behind a nation riddled with debt and economic hardship.

One of the most glaring symbols of this unfulfilled promise lies in the state of Nigeria’s refineries.

The Refinery Conundrum

Nigeria boasts four major state-owned refineries – two in Port Harcourt, one in Warri, and one in Kaduna. Together, these facilities have the capacity to process over 445,000 barrels of oil per day – more than enough to meet domestic demand.

Yet, for years, these refineries have stood moribund – rusting monuments to mismanagement and neglect. Plagued by poor maintenance, outdated technology, and allegations that they operate far below capacity – if they operate at all.

This failure in domestic refining capacity has led to a cruel irony: Nigeria, an oil-rich nation, relies heavily on imported fuel to meet its energy needs.

The Subsidy Trap

To manage the impact of its refining shortfall and reliance on imported fuel, successive Nigerian governments implemented an oil subsidy program. The intention was noble – to shield citizens from the full impact of global oil price fluctuations. However, this policy became a double-edged sword.

While it provided some relief to consumers, the subsidy program drained billions of dollars from the national budget annually. It also created opportunities for fraud and corruption, with unscrupulous operators exploiting the system for personal gain.

By 2023, the Tinubu-led administration made the decision to bring an end, roughly 49 years of oil subsidy.

What Changed? Tying the Past to the Present and the Future

The question of what changed is one that Nigerians have been grappling with for decades. The oil boom of the 1970s was a time of great promise, but it was also a time of missed opportunities.

The wealth that flowed into the country could have been used to build a diversified economy, one that was not solely dependent on oil. It could have been used to develop human capital, to invest in education, healthcare, and infrastructure that would have set the stage for sustainable development.

Instead, that wealth was squandered. The focus on oil led to the neglect of other sectors, and the corruption that took root during the boom years has proven difficult to uproot.

The long queues at petrol stations, the high fuel prices, and the ongoing debates about subsidy removal are all, in many ways, consequences of decisions made and opportunities missed during those heady days.

As Nigerians face the challenges of today including the long queues at petrol stations, the rising cost of fuel, the hike in transportation costs, and its inevitable effect on the price of goods and services, it is clear that the legacy of the oil boom still looms large. The story of the oil boom is not just a story of what went wrong; it is also a reminder of what could have been, and what still can be, if the lessons of history are heeded.

Reflections, Reflections, Reflections

Despite the challenges, Nigeria remains a nation rich in resources, both natural and human. The key to unlocking that potential lies not in the ground beneath our feet, but in our ability to learn from the past, fix our institutions, and chart a new course for the future.

The Dangote Refinery, with its promise of reducing Nigeria’s dependence on imported fuel, is reminiscent of the grand projects of the 1970s. But the lessons of the past are clear: without good governance, transparency, and a commitment to diversifying the economy, even the most ambitious projects can fail to deliver on their promise.

As we reflect on the oil boom of the 1970s, let us do so with an eye to the future — a future where the mistakes of the past are not repeated, and where the wealth of the nation is used to build a prosperous and equitable society once and for all.

Bravewood is licensed by the Central Bank of Nigeria to provide investments with low risk and high returns for Nigerian professionals.